Limestone from southern Pennsylvania

By Laura Turner Igoe

As a curator and art historian who has written about the material ecologies of American art and culture, I find that my understanding of artwork is always enriched by working directly with materials. Recent exhibitions and a growing collection of ceramic pieces at the James A. Michener Art Museum, where I work, inspired me to take ceramics classes at my local art center in order to better comprehend how the vessels and sculptural forms in our galleries were created.

When sitting in a ceramics studio in front of a hunk of clay, it is easy to conceive of the medium as simple and wholesome, harmoniously connected to the earth and unrelated to industrial technologies of extraction and refinement. Surrounded by buckets of raw materials and chemical mixes of glazes and slips, I realized that none of these would not be out of place in a laboratory or manufacturing plant. One such material is whiting, or calcium carbonate, a seemingly innocuous white powder that, when added in small amounts to glazes, can reduce clay shrinkage when firing, whiten low-fire clay bodies, and increase glaze hardness. Calcium carbonate, however, is all around us.

The geologic source of calcium carbonate—limestone—connects this material to one of the most widely used materials on Earth, second only to water: cement. Both cement and calcium carbonate are the direct, extracted products of limestone. To create cement, crushed limestone ore is first heated, driving off carbon dioxide and turning it into lime. In ceramics, this heating and off-gassing simply happens later, during firing. Calcium carbonate is otherwise integral to many of the items we use and consume on a daily basis, including papers, plastics, adhesives, sealants, mortar, and even medicine and antacid tablets. It is therefore a material that surrounds and permeates our bodies. This is especially poignant when we consider that calcium carbonate, extracted from limestone, is itself biochemical in origin. Limestone is formed by the slow compaction of decomposed shellfish and corals over hundreds of millions of years. This combination of pressure and deep time transforms living organisms into sedimentary rock.

Image of a limestone cave

Photo Credit Marko Milivojevic

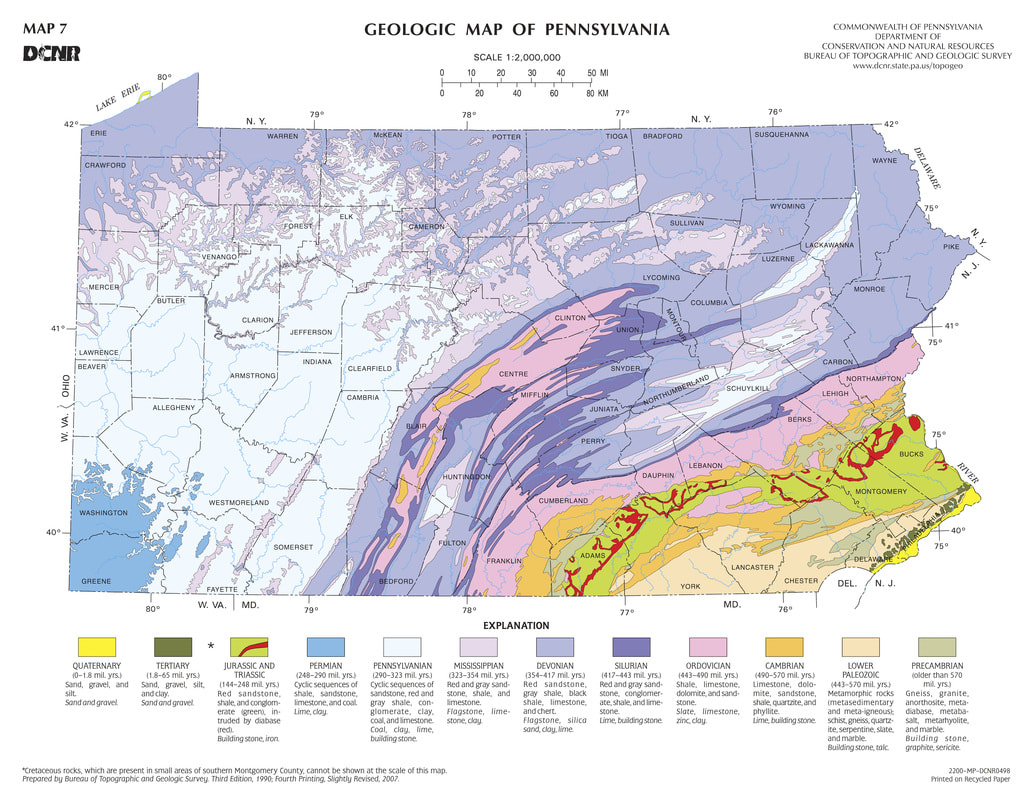

Rocky Mountain Clay, a clay supplier in Denver, Colorado, sources its whiting from a mining operation close to my own home: Pennsy Supply Inc. in York and Lancaster counties in southeastern Pennsylvania. There, open pit mines carve into deposits some 250-540 million years old. Limestone is an important resource for Pennsylvania and is a part of the commonwealth’s booming nonfuel-mineral industry. Mining for limestone, however, can devastate local environments through habitat loss, high noise levels, dust emissions, and water pollution.

The 2015 Directory of Nonfuel-Mineral Produce in Pennsylvania draws a direct comparison between this industry and early ceramics production and nation-building. It explains that nonfuel-mineral commodities, “have been important in Pennsylvania for many centuries, from the earliest crafting of pottery and other objects by the Native American population though William Penn’s instruction to the earliest settlers of Philadelphia to build their homes of brick for fire resistance.”[1] Such a comparison positions extraction industries like limestone mining as deeply tied to the commonwealth’s history and identity, even though the establishment of limestone mines followed the decimation and displacement of Pennsylvania’s Indigenous peoples through broken agreements, genocide, and disease.

Calcium carbonate’s use in ceramics is miniscule compared the consumption of cement the material’s deployment in other industries. While ceramics is not the primary driver of extractive industries like limestone mining, however, it is nonetheless intimately entangled with them. A consideration of the environmental origins of materials like whiting, however, brings a new perspective to the glazes, powders, and other chemicals that line the shelves of a ceramics studio, making the medium much more complex and integrated to the industrial marketplace than one might originally suspect.

[1] John H. Barnes, Directory of Nonfuel-Mineral Producers in Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, 2015), preface.

Pennsys currently operates 2 “high quality calcium carbonate” mines in Pennsylvania.